Saturdays are for little road trips

Acquiring a William Morris book; becoming a Wilkie Collins fan

Online auction item pickup as excuse for weekend jaunt

Back when I had field biology jobs (many years ago), I spent massive amounts of time driving around on country roads. Some of it was getting between sampling sites; much was just meandering the backroads, looking for plausible habitat.

I loved it. I remember deciding silently, and based on I don’t know what, that the perfect car trip length was four hours. The logic that got me there is lost to history, but I’ll maintain that a long car ride is a little holiday.

At the time of writing this, my best excuse for spending a weekend morning on the backroads is if I have to pick up an item I purchased from an online auction.

Highly recommended excuse! Here’s the how-to:

Log onto an online auction site like Maxsold.

Find an auction with a pickup location about one hour out of town, ideally in a spot you never otherwise frequent.

Bid on a low-price item. You need to save your dollars for gas and Tim Hortons. (Ideally these will cost more than the thing you bought.)

Win the item. (Optional: Hum a happy little I-won-the-item tune.)

On the designated Saturday or Sunday morning (abide by the schedule; people don’t seem to like randoms showing up to their house on the wrong day), walk your Gus early so you have plenty of time to get to the pickup location.

Plug the route into Google Maps or equivalent.

Immediately disobey Google Maps’ directions by driving to the nearest Tim Hortons. Purchase your beverage. (In winter, I recommend a Steeped Tea™; in summer, the weak among us may want to switch to an iced coffee.)

Choose an audiobook or podcast for the road.

Embark on your two-hour adventure!

Note the essential nature of a pitstop at Tim’s. While I will allow that it’s technically possible to complete the mission with a travel mug of coffee from home, and even that I have done this, picking up your little Timmies treat is part of the experience and ought not to be neglected.

Regarding the unfamiliar countryside house at the pickup location, you may be asking, “Will I be murdered?” In my experience, no. I’m pretty sure Maxsold would get bad reviews if you were. Take heart.

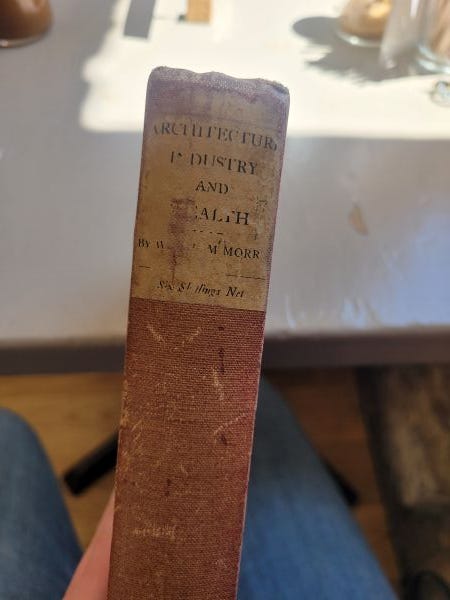

This past weekend, I took a super pleasant jaunt out to the Lanark countryside west of Ottawa (also known to locals as maple syrup and cheddar cheese territory). My quarry was 1902 edition of some William Morris essays on architecture and design. (The Internet Archive has a copy scanned in, if you want to peruse.)

Longtime readers1 may recall that I’d previously rejected an old copy of Morris’s Atalanta’s Race for being too expensive and too Atalanta’s Race (which I’m not sure I like enough to justify a fancy copy). No problem this time: the auctioned collection cost me eight Canadian bucks, which is a darn good price, and it had to do with his thoughts on design, which I am definitely interested in.

So far in my reading, Morris has offered that the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul is beautiful and that St. Peter’s in Rome is ugly. As an ignorant boob, I currently find them both beautiful, but I’m willing to learn.

Meanwhile, I’ll somewhat contradict an earlier post by saying it can be pretty pleasant to read from an old, rare copy of a book covered in foxing and smelling of vanilla. Sue me.2

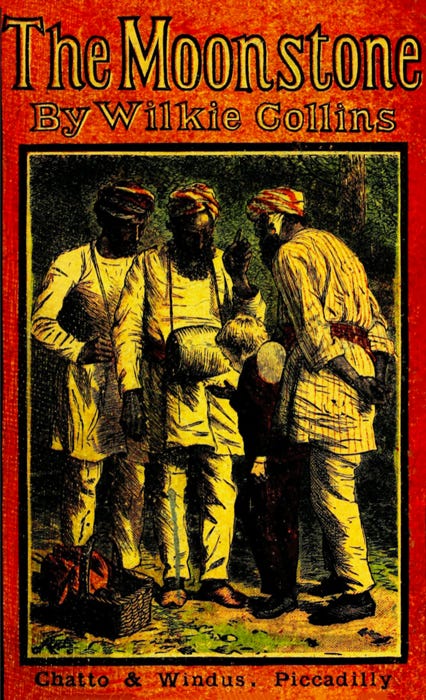

Late to the Moonstone party

More on this perhaps later, but part of my sustenance on the Morris-book-pickup mission was the audiobook of The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins. This was my first time reading it. I guess I’ve been familiar with the plot since childhood, as there was a Wishbone episode based on it, but otherwise it never seemed to insist on being read.

It should have insisted! What a winner.

I think I had an idea that The Moonstone, an 1868 novel about a stolen diamond, was meant to be interesting primarily in being one of the earliest detective novels and in establishing many of the genre conventions. A lot of books stay relevant by being proto-somethings. They’re in the dusty, beige, “of scholarly interest” category.3 It’s unlikely many people would read them for their own sake.

In short, I had The Moonstone unfairly slotted into this category. Eventually I guess I decided to read it out of some sense of Victorian completionism.

Joke’s on me! Turns out it’s relentlessly entertaining.

Case in point: One of the first-person narrators is an interfering evangelical spinster named Miss Clack. She’s dedicated to a charity called the Mothers’-Small-Clothes-Conversion-Society. The aim of this charity is to acquire trousers pawned by wastrel fathers and, as a lesson to them, take the trousers apart and remake them into little-boy trousers:

We had a meeting that evening of the Select Committee of the Mothers’-Small-Clothes-Conversion-Society. The object of this excellent Charity is—as all serious people know—to rescue unredeemed fathers’ trousers from the pawnbroker, and to prevent their resumption, on the part of the irreclaimable parent, by abridging them immediately to suit the proportions of the innocent son.

If you’ve encountered funnier premises recently than a charity dedicated to making dads’ pants small—buddy, I want to hear about it.

This book was also great for constantly bringing up things I wanted to talk about in an English lit seminar (or, I guess, in an essay, if in a wilderness without seminars). If you’ve studied English literature,4 you know that observing something interesting about a work of literature is a necessary but insufficient point in contributing the discourse. You have to have something to say about it.

Having as yet no arguments to make, however, and just in the interest of noodling on things with people, here are a few of the notes I jotted down on things I would try to discuss with people, if I could, if we were all in a seminar on The Moonstone:

One of the narrators of the book is Mr. Betteredge, a servant in the household where the robbery takes place. He muses early in the book on the gentry’s intellectual pursuits as the fruit of idleness and a big inconvenience to servants:

Nine times out of ten they take to torturing something, or to spoiling something—and they firmly believe they are improving their minds, when the plain truth is, they are only making a mess in the house. … Sometimes, again, you see them occupied for hours together in spoiling a pretty flower with pointed instruments, out of a stupid curiosity to know what the flower is made of. Is its colour any prettier, or its scent any sweeter, when you do know? But there! the poor souls must get through the time, you see—they must get through the time. … In the one case and in the other, the secret of it is, that you have got nothing to think of in your poor empty head, and nothing to do with your poor idle hands.

This got me thinking about presentations of idleness versus leisure of the Josef Pieper sort. (Would Betteredge admit that there is a distinction? I’m not sure.) It’s worth noting that Betteredge is a comical character and a lot of his ideas are highly eccentric; still, he’s a very sympathetic figure in the story. It’s also Collins who gives him his voice: arguably, the work of an author of detective stories falls into just the category of inconsiderate and unnecessary intellectual pursuit Betteredge is lamenting. Or maybe not. Do the relationships of characters of various classes to leisure/idleness in this story speak to their access to the events behind the mystery? A scientific experiment, for instance, proves essential in partially solving the case (though only partially). Servants are essential at every step. Or am I reaching here? Should the prof dismiss this question (or cleverly refocus it)? Discuss.

One of the clues in the mystery is a smudge in the paint on the door of a bedroom. An investigator proposes early on that it was made by the petticoats of one of many women crowding into the room with him. The fact that it’s not immediately clear whose petticoats might be the culprit gave me pause: in this story, everybody in the household wears long skirts (whether long petticoats or, for men, a nightgown). Not so in other places or other moments in history—the nature of the confusion is sort of inherently pre-Edwardian. What would be the equivalent garment or accessory today? Is there one? Is dress in, say, North America today so non-standardized that we can’t think of an equivalent situation? I’m imagining a mystery where the detective establishes that the culprit was wearing an orange shirt, then learns that everyone in the building wears a uniform with an orange shirt. Mainly, though, it’s neat to me that the mystery is fashion-dependent, though it certainly doesn’t seem self-conscious in this respect. Discuss.

This story strikes me as remarkably non-Christian in its trappings, if not in its principles. (I say this as a Christian who really liked it.) I realize mainstream Victorian culture was certainly defined by Christianity (I leave it to those wiser than me to argue how authentically or superficially), and that this book is a product of its context in many respects. But it’s also post-Christian (para-Christian?) in ways that feel to me very nineteenth-century. The Moonstone features only one central character deeply devoted to Christianity (Miss Clack, she of the abridged pants), and she’s ridiculous. Mr. Betteredge constantly consults Robinson Crusoe as a prophetic text, and while this is comical, it also seems to serve him just as well as a Bible might. Also, the aims and complaints of the three Hindu gentlemen trying to reclaim the diamond (stolen centuries ago from a statue of a god in their temple in India) are treated, I thought, very sympathetically, particularly at the end of the story. (“Are you suggesting this is an orientalism- and colonialism-free work, Nat?” Of course not. Queen Victoria scoffs at you.) What do we make of this? Discuss.

Do we think Wilkie Collins knew what the solution to the mystery would be when he started writing this? (It’s possible this is a question that can be answered definitively; I’ll Google it in a moment.) The Moonstone was published serially, meaning he might have been able to change how it ended right up until the final instalment was printed. My hunch is that he had one idea, but then abandoned it in favour of a twist—or maybe that he had a sense of who the thief would be but wasn’t sure how to get there from the initial description of the theft. The first half of the book just feels much more solidly mortised together than the later parts that reveal the (somewhat improbable) solution. The twist works, but it feels like something had to be squeezed into place that didn’t quite fit. I should probably interrogate my impressions in this respect a little further. In the meantime, do we have an impression either way? What’s the cause of that impression? Discuss.

Update: Very quick Googling produces this Wikipedia item:

The final novel was serialised … from 4 January to 8 August 1868… This period was affected by several difficulties in Collins’ life. His mother, Harriet Collins, died on 19 March 1868, and his presence at her bedside caused the novel to fall behind schedule. He also began to suffer a painful attack of gout, which he described in a preface to the 1871 edition as “the bitterest affliction of my life and the severest illness from which I have ever suffered”. To dull the pain, Collins took large amounts of laudanum, resulting in portions of the novel to be written in a drug-induced haze. He would later comment that he did not recall writing these passages.

This doesn’t exactly answer the question, but the fact that Collins was becoming increasingly familiar with the effects of laudanum as he wrote the book is… suggestive, at the very least, if you know the story.

There were other points, but in the interest of keeping you interested, I’ll stop here.

Anyway, if you’re at all intrigued by any of these questions about the book or have ones of your own, make sure to start a discussion. They’re calling it the summer of Wilkie.

Hits du jour

Here are a few of the things I’ve been enjoying lately (perhaps obviously, nary an affiliate link to be had round these parts):

The Paris Review recently published a bunch of essays on Jane Austen’s novels. I already shared

’s Northanger Abbey piece as a note, but here it is again. (It’s great.) I was also super intrigued by Jennifer Egan’s essay on Emma, largely because it acknowledged a history of the book’s being read in the tradition of mystery stories. Extremely good timing in terms of my reading this comment, as I’d just been listening to Emma and thinking, “This reads more like a mystery every time I read it.” Vindication! Though it’s a funny kind of mystery, since the heroine seems to be convinced there is no mystery, confident as she is in her own judgment. The reader is less sure. Emma is probably more bowled over than we are when all the truths are brought to light. In that respect it’s like the (amazing) novel Abigail by Magda Szabó, though also the opposite of it: the heroine of Abigail remains convinced almost until the end that the identity of “Abigail” hasn’t been firmly established, whereas the reader probably figured it out halfway through the story.My fiancé John sent me this podcast episode from EconTalk on sexual selection in birds. It’s great. Recommended if you love birds OR if you haven’t given them much thought lately—time to be amazed.

I recently learned that Better Homes & Gardens has a whole host of free garden plans on their website. As a very inexpert gardener, this was amazing to learn. I feel very trepidatious about planting certain plants together, especially perennials, not knowing how they’ll get on together (biologically and aesthetically). A great resource for those of us who need a bit of help.

Lately I’ve been collecting cut flowers from my garden to enjoy inside. I think I had an idea that we shouldn’t do this—that flowers were meant to be enjoyed in their living state. But I have learned that a lot of them tend to flower more when they’re cut (as the plant gets a stress signal), so I’ve decided to do my part. Was I influenced by the fact that assenting to this conclusion meant I could bring pretty flowers inside? Impossible to say. But they sure smell nice.

That’s all for now, friends.

As in, you’ve been here for more than two weeks.

N.B., I have spent all my money on books.

My tastes have been known to run to the dusty and beige.

Or possibly any language’s literature? I wonder how universal this is.