Journal of Permanently Unpublished Literature

Where do deleted scenes go when they die? (Also, some hits du jour)

The afterlife of abandoned drafts

I’ve curated my feeds on Substack and Twitter such that I rarely get a direct sighting of A Discourse, but only glimpses of its peripheral ripples. I highly recommend this approach. It makes one’s internet neighborhood very livable.

I mention this mainly because I’m aware that there have been various MFA-related Discourses circulating, and while this post touches on MFA writing, I’m pretty sure it bears no relation to any such conversations. But I might be wrong! Feel free to loop me in if you know otherwise.

What I want to poke at in this case is writing that gets abandoned sometime after somebody else reads it it. I got to thinking about this while recalling some of the excerpts of pieces my MFA classmates shared in workshop (way back in ancient times, from 2011 to 2013) and which, to the best of my knowledge, were never published.

In particular, I was thinking about this one scene from a novel my classmate was working on at the time. It was (from what I recall) set in contemporary Montreal and followed a passel of directionless graduate students, the way a lot of MFA novels follow a passel of directionless graduate students. It also featured what remains one of the funniest scenes I can remember reading anywhere.

Obviously I don’t have this scene handy to quote, and I suppose that even if I did, it would be wrong of me to reproduce it here. But the basic gist of it was that the grad students were at a party, and a bunch of them started talking about Jorge Luis Borges, except they were all attempting to correct one another’s pronunciation of “Borges.” What made the scene transcendent, though, was that the author never phonetically spelled what they were saying, but just kept writing “Borges,” so it just went like,

“I think it’s pronounced ‘Borges.’”

“It’s ‘Borges.’ He’s Argentinean.”

“I did my MA on his literary criticism. It’s ‘Borges.’”

Et cetera, et cetera. I can’t do it justice. It was absurd, wonderfully meta-fictional, infinitely clever, and just worked perfectly in the kind of book my classmate was writing. And as far as I’m aware, I can’t possibly get my hands on this scene, because I don’t think he ever published that book.

There are lots of pieces like that that I’ve encountered in workshops—ones that still rattle around in my memory, and that I wish I could reference more directly, but which don’t really “exist” in the publishing-world sense. Sometimes they’re from abandoned projects; sometimes they’re abandoned scenes in a project that turned into something wholly different. So what I’m left with is this kind of ghost canon of pieces I can remember, and which might even be impacting my approach to fiction without my knowing it, but which their own authors might disavow, for all I know.

What do you do with those bits of reading, in your mental library? It now seems incredibly clever (Ah, she had a plan) that I’ve already brought Borges into this post, “Library of Babel”-wise. It does feel like, if you’re somebody who’s accompanied other writers through their writing process, there might be this immaterial library in your mind, one full of not just all the books that you’ve ever read or heard about, but also of all the abandoned versions of those books—the books they almost were, before they were rewritten as something else—and also of all the books that got half-written, or through only a first draft, or got sent to agents and editors but were never picked up. … Or, to return to what brought me here, of pieces that were shared as workshop submissions but were never published thereafter.

I suspect the term “ghost canon” is one somebody’s already used for something more important, so I won’t insist on it, but they do haunt you, those little bits of un-cite-able stories. It’s not just that they weren’t published, but that in many cases their authors wouldn’t ever want them to be published. Maybe they deliberately destroyed all copies. You’re not supposed to be able to reference them.

If you write fiction, you also have some version of this with respect to your own work. For example, there were earlier drafts of what became my first published book that included not just completely different scenes, but a completely different ending. The original ending was objectively bad and I hope no one ever gets their hands on it. (That said, at least a few people did read it, so I have to allow that it has a ghostly existence of some kind.) Some of the deleted scenes were not bad at all, but were either working against the pace of the story or just weren’t essential to what I eventually realized the book wanted to be.

I know some authors hold on to such deleted scenes and share them as promotional material or patron perks. As things stand, I can’t imagine doing that. The book became what it became. Whatever debitage1 fell to the sides in the process of finding that version of the book was not meant to see the light of day, and I don’t plan to hang onto it.

Then again, I know some of my early readers—my brother, for instance—have told me that among those deleted scenes were their favourites in the book. While they understand the choice to exclude them, they remember them fondly. So what does that mean for those scenes? They have a kind of afterlife, I guess. I can’t unmake them.

You start thinking about this, as with most things, and the implications spiral outward. (“Define your scope,” your project supervisor tells you, but you cannot hear him, for he does not exist.) For example, for the historically minded, this doesn’t even begin to deal with the fact that publishing’s claim to imbue authority is, in a sense, specific to a span of human history—say, early modernity onward—and that it doesn’t speak to how ancient or medieval texts began to circulate. Even some modern texts that found their way into the standard literary canon might have been circulated (initially) only among friends; they were meant to be ephemeral. We know publication is neither necessarily an author’s end-goal nor the final word.

Get this far into the problem, and you begin also to think about how oral storytelling fits into things. Do those ghostly manuscripts live in the same space as the unwritten stories I’ve listened to? I’m not sure. Memory as librarian is playing a big role in both cases. But the one might be a story someone really wanted me to remember, and the other might be very much the opposite.

It’s interesting, the ways you do or don’t come back to what an author wanted you to consider theirs. The more you work on the literary creation side of the equation, the more you come to think of the published version of a piece not as the inevitable final product, but as a version of the work that got “locked” at a certain point but which might have been any number of other things. I even brought up on Substack recently (in one of my Hits du jour sections) the idiosyncratic approach the editors of J.R.R. Tolkien’s collected poems took in building that work. What do you do when most of the poems were never published, and many existed in multiple drafts, no one of which is clearly the author’s preferred final version? At least one approach, it turns out, is simply to include every version. And even this is only possible because Professor T. was no notebook-burner.

I suspect someone in the editing world, or perhaps in the creative writing studies world (nascent little micro-world that it is), has commented on this phenomenon of a ghostly canon in much greater depth and with much clearer insight (and has probably given it a better name). If you know of any such takes, please let me know. Meanwhile, this post is offered in the spirit of positing a problem and meandering through its implications rather than staking a claim. (“Ah, the coward’s approach,” you say. Well,,)

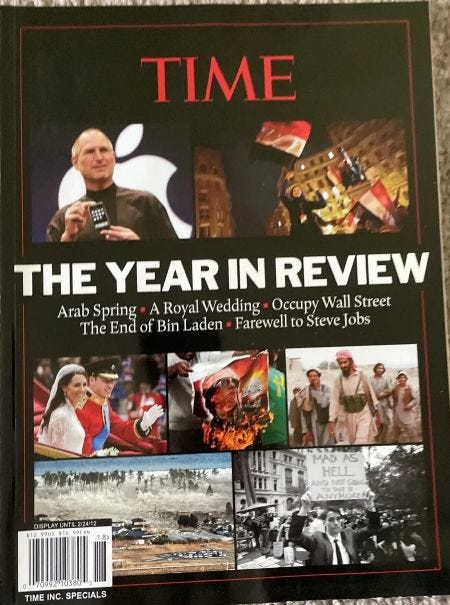

Hits du jour

Some things I’ve been liking lately:

Before I got to thinking about being haunted by abandoned scenes, I’d had some unrelated thoughts I supposed I might write about on Substack, thoughts that arose from visiting the Michener Art Museum in Doylestown, PA, with John a couple days ago. That post may or may not be worth writing (I feel it’s best to embrace an abundance mindset with post topics—no need to hoard old ideas; new ones will come), but in the meantime: a cool art gallery. Some 19th-century stuff, some contemporary; lots of nice benches. Also: it’s across the street from the truly bizarre Fonthill Castle, a huge castle-like building made entirely of concrete (including the roof!). I realize there are hungry children in the world, but a (perhaps disordered) part of me can’t help rejoicing when the occasional rich weirdo decides to use his money to leave behind something completely odd and superfluous, like an elaborate monument to his love of concrete.

We just made the smashed cucumber salad from J. Kenji López-Alt’s cookbook The Wok, and it was fantastic. The version of the salad I can find online under López-Alt’s name seems more minimal, whereas this version from The Woks of Life seems more or less like the one in the cookbook. Anyway, it’s great. A summertime treat, and receives a thumbs up from John who typically hates raw vegetables.

To give John further credit for bringing neat things into my life this week: Two cool (old) albums I’ve enjoyed, per J.’s recommendation, have been Bruce Springsteen’s The Seeger Sessions (2006) and DJ Danger Mouse’s The Grey Album (2004). I’m very late to both parties (though I realized I’d heard certain songs from the former, just never the full album), so I share this to tell on myself and also because sometimes a whole bunch of us turn up late to the same party. Anyway, the Springsteen one is all Pete Seeger/American folk revival tunes, and it’s fantastic. Get up and dance. The latter is a mashup of the Beatles’ The White Album with Jay-Z’s The Black Album, and it can make its creator zero money thanks (?) to copyright rules, but it is exceptional early 2000s listening.

The Public Domain Review posted an article looking at the historical difficulties of including “X” in English alphabet books. As a friend of mine said on Facebook, “This kind of content is why I come to the internet.”

That’s all for now, amigos.

Thanks to University of Saint Thomas MFA alumna Valoree Dowell for introducing me to this word. I got to work with her on her MFA thesis project that took it as its title. May that book promptly enter the standard library of published works.

“Ghost canon” — that’s so perfectly apt, Natalie. I carry so many ghosts — published or not, they’ve built me in way, word by word.

I like the term "ghost canon"! It perfectly describes what you're getting at- that inner library of unpublished bits of pieces. I think about the masterful writing of my MA workshop peers on a regular basis, and they are always just... out of reach...